After Thomas Mann’s novel

After Thomas Mann’s novel

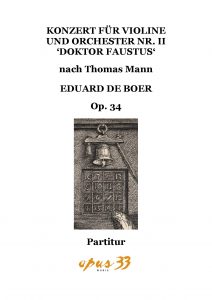

I. Andante amoroso

II. Scherzo. Presto molto agitato –

III. Tema con Variazioni

Commissioned by Steven Hond

INTRODUCTION

It had for a long time been a deep wish of mine to compose a violin concerto according to how Thomas Mann describes Adrian Leverkühn’s concerto in his novel ‘Doktor Faustus’; a concerto that, according to the novel, Leverkühn wrote in the early twenties of the 20th century. Eventually, Steven Hond, at the time a friend of mine and director of a large printing company, enabled me to compose the piece; which I did between 1994 and 2001, whenever I had some ‘spare time’. I have tried to follow as closely as possible the various descriptions of the concerto as they appear in Thomas Mann’s novel, see below.

So far, the concerto hasn’t been performed. In 2020, as a result of the ‘pandemic situation’, I had time to prepare a sound file of the concerto, using the program Note Performer for this.

Eduard de Boer, November 2020

I. Excerpts from Thomas Mann’s novel…

From Chapter XXXIII, p. 510:

Und plötzlich (…) kam Rudi auf das Violin-Konzert zu sprechen (…). „Wunderbar würden Sie es machen, (…) – mit einem unerhört einfachen und sangbaren ersten Thema im Hauptsatz, das nach der Kadenz wieder einsetzt, – das ist immer der beste Augenblick im Klassischen Violin-Konzert, wenn nach der Solo-Akrobatik das erste Thema wieder einsetzt. Aber Sie brauchen es garnicht so zu machen, Sie brauchen überhaupt keine Kadenz zu machen, das ist ja ein Zopf. Sie können alle Konventionen umstoßen und auch die Satz-Einteilung, – es braucht gar keine Sätze zu haben, meinetwegen könnte das Allegro molto in der Mitte stehen, ein wahrer Teufelstriller, bei dem du mit dem Rhythmus jonglierst, wie nur Sie es können, und das Adagio könnte am Schluß kommen, als Verklärung, – es könnte alles gar nicht unkonventionell genug sein, und jedenfalls wollte ich es hinlegen, daß den Leuten die Augen übergehen.“

And suddenly (…) Rudi came to speak of the violin concerto (…). “And you would do it wonderfully (…) — with an unheard-of simple and singable first theme in the main movement that comes in again after the cadenza. That is always the best moment in the classic violin concerto, when after the solo acrobatics the first theme comes in again. But you don’t need to do it like that, you don’t need to have a cadenza at all, that is just a convention. You can throw them all overboard, even the arrangement of the movements, it doesn’t need to have any movements, for my part you can have the allegro molto in the middle, a real ‘Devil’s trill,’ and you can juggle with the rhythm, as only you can do, and the adagio can come at the end, as transfiguration — it couldn’t be too unconventional, and anyhow I want to put that down, that it will make people cry. ”

From Chapter XXXVI, p. 572 – 73:|

Er war damals, Frühjahr 1924, in Wien, wo, im Ehrbarsaal und im Rahmen eines der sogenannten „Anbruch-Abende“, Rudi Schwerdtfeger das endlich für ihn geschriebene Violin-Konzert mit starkem Erfolg – nicht zuletzt für ihn selbst – zum erstenmal gespielt hatte. Ich sage: „ nicht zuletzt” und meine „vor allem“, denn eine gewisse Konzentration des Interesses auf die Kunst des Interpreten liegt geradezu in den Absichten des Werkes, das, bei aller Unverkennbarkeit der musikalischen Handschrift, nicht zu Leverkühns höchsten und stolzesten gehört, sondern, wenigstens partieenweise, etwas Verbindliches, Kondeszendierendes, ich sage besser: Herablassendes hat (…).

He was then, in the spring of 1924, in Vienna, where in the Ehrbar Hall and in the setting of one of the so-called Anbruch evenings Rudi Schwerdtfeger at last and finally played the violin concerto written for him. It was a great success, not least for Rudi himself. I say not least, and mean above all; for a certain concentration of interest on the art of the interpreter is inherent in the intention of the work, which, though the hand of the musician is unmistakable, is not one of Leverkühn’s highest and proudest effects, but at least in part has something complimentary and condescending (…).

From Chapter XXXVIII, p. 592 – 95:

Meine Leser sind unterrichtet darüber, daß Adrian das jahrelang beharrlich gehegte und geäußerte Anliegen Rudi Schwerdtfegers erfüllt und ihm ein Violin-Konzert auf den Leib geschrieben, ihm das glänzende, geigerisch außerordentlich dankbare Stück auch persönlich zugeeignet und ihn sogar nach Wien zur Erstaufführung begleitet hatte. (…) Dem zuvor aber möchte ich (…) auf die (…) Kennzeichnung zurückkommen, die ich weiter oben dieser Komposition zuteil werden ließ, des Sinnes, sie falle durch eine gewisse Verbindliche virtuos-konzertante Willfährichkeit der musikalischen Haltung ein wenig aus dem Rahmen von Leverkühns unerbittlich radikalem und zugeständnislosem Gesamtwerk. (…)

Es ist ein Besonderes mit dem Stück: In drei Sätzen geschrieben, führt es kein Vorzeichen, doch sind, wenn ich mich so ausdrücken darf, drei Tonalitäten darin eingebaut, B-dur, C-dur und D-dur, – von denen, wie der Musiker sieht, das D-dur eine Art von Dominante zweiten Grades, das B-dur eine Subdominante bildet, während das C-dur das genaue Mitte Hält. Zwischen diesen Tonarten nun spielt das Werk sich aufs kunstreichste, so, daß die längste Zeit keine von ihnen klar in Kraft gesetzt, sondern jede nur durch Proportionen zwischen den Klängen angedeutet ist. Durch weite Komplexe hin sind alle drei überlagert, bis endlich, auf eine allerdings triumphale, jedes Konzertpublikum elektrisierende Weise, C-dur sich offen erklärt. Es gibt da, im ersten Satz, der „Andante amoroso“ überschrieben und von einer ständlich an der Grenze des Spottes gehaltene Süße und Zärtlichkeit ist, einen Leitakkord, der für mein Ohr etwas Französisches hat: c-g-e-b-d-fis-a, ein Zusammenklang, der, mit dem hohen f der Geige darüber, wie man sieht, die tonischen Dreiklänge jener drei Haupt-Tonarten in sich enthält. In ihm hat man sozusagen die Seele des Werkes, man hat in ihm auch die Seele des Hauptthemas dieses Satzes, das im dritten, einer bunten Variationsfolge, wieder aufgenommen wird. Es ist ein in seiner Art wundervoller melodischer Wurf, eine rauschende, in großem Bogen sich sich hintragende, sinnbenehmende Kantilene, die entschieden etwas Etalagehaftes, Prunkendes hat, dazu eine Melancholie, der es an Gefälligkeit, nach dem Sinne des Spielers, nicht fehlt. Das Charakterisch-Entzückende der Erfindung ist das unerwartete uns zart akzentuierte Sich-Übersteigern der auf einen gewissen Höhepunkt gelangten melodischen Linie um eine weitere Tonstufe, vor der sie dann, mit höchstem Geschmack, vielleicht allzu viel Geschmack geführt, zurückflutend sich aussingt. Es ist eine der schon körperlich wirkenden, Haupt und Schultern hinnehmenden, das „Himmlische“ streifenden Schönheitsmanifestationen, deren nur die Musik und sonst keine Kunst fähig ist. Und die Tutti-Verherrlichung eben dieses Themas im letzten Teil des Variationensatzes bringt den Ausbruch ins offene C-dur. Dem Eclat voran geht eine Art von kühnem Anlauf in dramatischem Parlando-Charakter, – eine deutliche Reminiszens an das Rezitativ der Primgeige im letzten Satz von Beethovens A-moll-Quartett, – nur das auf die großartige Phrase dort etwas Anderes folgt als eine melodische Festivität, in der die Parodie des Hinreißenden ganz ernst gemeinte und darum irgendwie beschämend wirkende Leidenschaft wird.

Ich weiß, daß Leverkühn, ehe er das Stück komponierte, die Violinbehandlung bei Bériot, Vieuxtemps und Wieniawski genau studiert hat, und in einer halb respektvollen, halb karikaturistischen Weise wendet er sie an, – übrigens unter solchen Zumutungen an die Technik des Spielers, besonders in dem äußerst ausgelassenen und virtuosen Mittelsatz, einem Scherzo, worin sich ein Zitat aus Tartinis Teufelstriller-Sonate findet, das der gute Rudi sein Äußerstes aufzubieten hatte, um den Anforderungen gerecht zu werden: Der Schweiß perlte jedesmal, wenn er die Aufgabe durchgeführt, unter seinem lockig aufstrebenden Blondhaar, und das Weiße seiner hübschen zyanenblauen Augen war von rotem Geäder durchzogen. Aber wieviel Schadloshaltung, freilich, wieviel Gelegenheit zum „Flirt” in einem gesteigerten Sinn des Wortes war ihm gewährt in einem Werk, das ich in das Gesicht des Meisters hinein die „Apotheose der Salonmusik” genannt habe, im Voraus gewiß, daß er mir die Kennzeichnung nicht verübeln, sondern sie mit Lächeln aufnehmen würde.

My readers are aware that Adrian in the end complied with Rudi Schwerdtfeger’s long-cherished and expressed desire, and wrote for him a violin concerto of his own. He dedicated to Rudi personally the brilliant composition, so extraordinarily suited to a violin technique, and even accompanied him to Vienna for the first performance. In its place I shall speak about the circumstance that some months later, towards the end of 1924, he was present at the later performances in Berne and Zürich. But first I should like to discuss with its very serious implications my earlier, perhaps premature – perhaps, coming from me, unfitting – critique of the concerto. I said that it falls somewhat out of the frame of Leverkühn ‘s ruthlessly radical and uncompromising work as a whole. (…)

There is one strange thing about the piece: cast in three movements, it has no key-signature, but, if I may so express myself, three tonalities are built into it: B-flat major, C major, and D major, of which, as a musician can see, the D major forms a sort of secondary dominant, the B-flat major a subdominant, while the C major keeps the strict middle. Now between these keys the work plays most ingeniously, so that for most of the time none of clearly comes into force but is only indicated by its proportional share in the general sound-complex. Throughout long and complicated sections all three are superimposed one above the other, until at last, in a way electrifying to any concert audience, C major openly and triumphantly declares itself. There, in the first movement, inscribed “andante amoroso,” of a dulcet tenderness bordering on mockery, there is a leading chord which to my ear has something French about it: c, g, e, b-flat, d, f-sharp, a, a harmony which, with the high f of the violin above it, contains, as one sees, the tonic chords of those three main keys. Here one has, so to speak, the soul of the work, also one has in it the soul of the main theme of this movement, which is taken up again in the third, a gay series of variations. In its way it is a wonderful stroke of melodic invention, a rich, intoxicating cantilena of great breadth, which decidedly has something showy about it, and also a melancholy that does not lack in grace if the performer so interpret it. The characteristically delightful thing about the invention is the unexpected and subtly accentuated rise of the melodic line after reaching a certain high climax1 by a further step, from which then, treated in the most perfect, perhaps all too perfect taste, it flutes and sings itself away. It is one of those physically effective manifestations capturing head and shoulders, bordering on the “heavenly,” of which only music and no other art is capable. And the tutti-glorification of just this theme in the last part of the variation movement brings the bursting out into the open C major. But just before it comes a bold flourish – a plain reminiscence of the first violin part leading to the finale of Beethoven’s A-minor Quartet; only that here the magnificent phrase is followed by something different, a feast of melody in which the parody of being carried away becomes a passion which is seriously meant and therefore creates a somewhat embarrassing effect.

I know that Leverkühn, before composing the piece, studied very carefully the management of the violin in Bériot, Vieuxtemps, and Wieniawski and then applied his knowledge in a way half-respectful, half caricature and moreover with such a challenge to the technique of the player – especially in the extremely abandoned and virtuoso middle movement, a scherzo, wherein there is a quotation from Tartini’s Devil’s Trill Sonata – that the good Rudi had his work cut out to be equal to the demands upon him. Beads of sweat stood out beneath his blond locks every time he performed it, and the whites of his pretty azure eyes were bloodshot. But how much he got out of it, how much opportunity for “flirtation” in a heightened sense of the word, lay in a work which I to the Master’s very face called “the apotheosis of salon music”! I was, of course, certain beforehand that he would not take the description amiss, but accept it with a smile.

From Chapter XL, p. 621:

Er nahm dem Violinisten die Geige weg und improvisierte (…) sehr großzügig darauf, indem er zum Auflachen der Unsrigen einige Griffe aus der Kadenz „seines“ Violinkonzerts einflocht.

He took the violinist’s fiddle away from him, and (…)improvised magnificently on it, weaving in, to the amusement of our party, some snatches from the cadenza of “his” concerto.

From Chapter XIX, p. 227:

So findet sich in den Tongeweben meines Freundes eine fünf- bis sechsköpfige Notenfolge, mit h beginnend, mit es endigend und mit wechselndem e und a dazwischen, auffallend häufig wieder, eine motivische Grundfigur von eigentümlich schwermütigem Gepräge, (…) zuerst in (…) dem herzzerwühlenden Liede „O lieb Mädel, wie schlecht bist du“, das ganz davon beherrscht ist (…). Es bedeutet aber diese Klang-Chiffre h e a e es: Hetaera esmeralda.

Thus in my friend’s musical fabric a five– to six-note series, beginning with B and ending on E flat, with a shifting E and A between, is found strikingly often, a basic figure of peculiarly nostalgic character, (…) at first in (…) the heart-piercing lied: “O lieb Madel, wie schlecht bist du,” which is permeated with it (…). The letters composing this note-cipher are: h, e, a, e, e flat: hetaera esmeralda.*

[* The English B is represented in German by H.]

English translations by H.T. Lowe-Porter

II. … and two quotations from other sources

In the beginning of the sixties there were, among the fanatic advocates of serialism, quite a few people who believed that Britten (…) kept composing in a „dead language“.

Donald Mitchell, 1997

My father (…) used to say, that if it ever came to some musical illustration of his novel Doktor Faustus, you would be the composer to do it.

Golo Mann to Benjamin Britten, September 14, 1970

Youtube (electronic sounds):